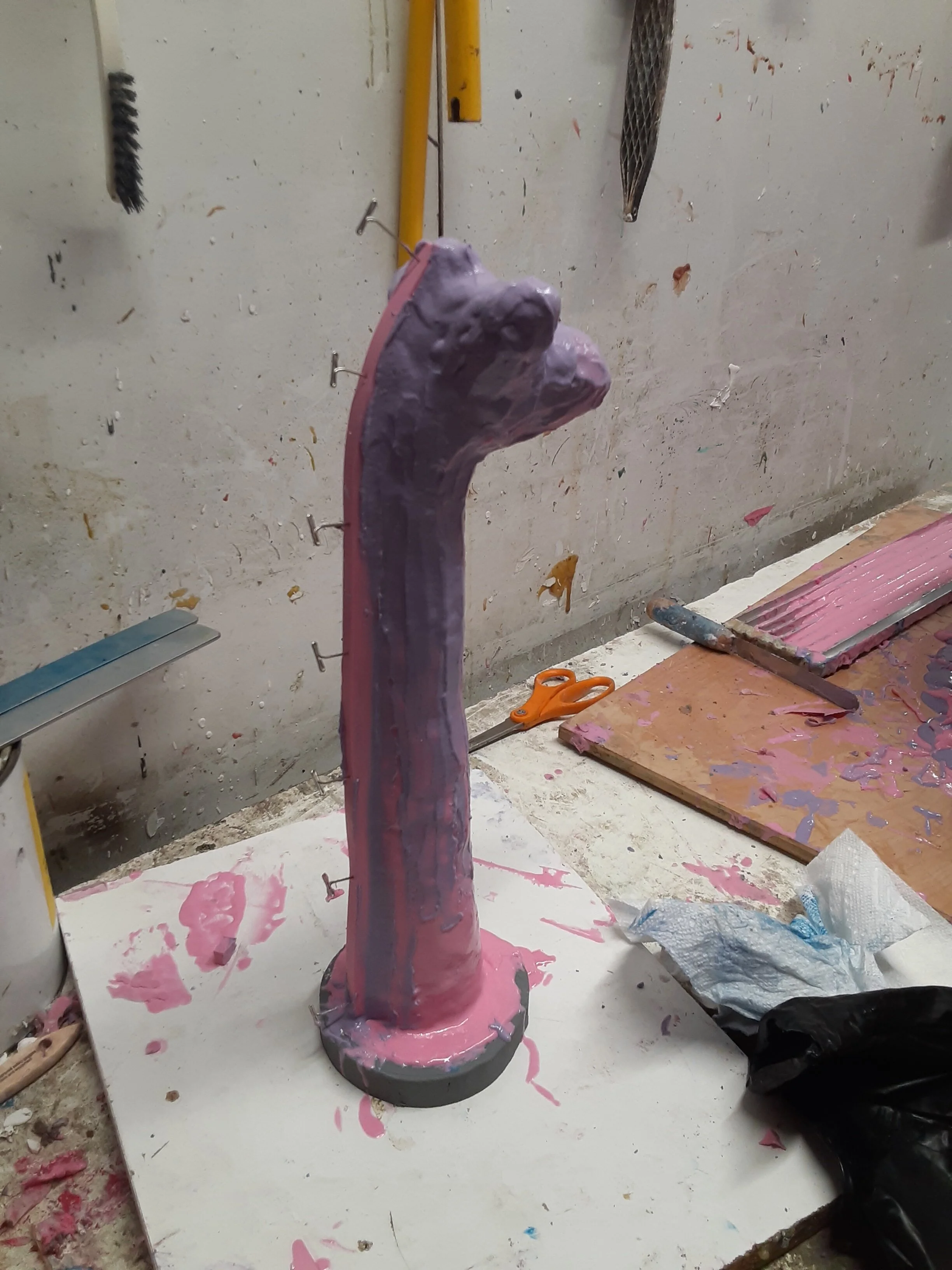

How is a sculpture cast into bronze? Refuge, pictured below, was made of in wax in my studio.

To transport it to the foundry for casting into bronze I needed to saw off the giraffe from the turtle. and separate all the figures. Here is the turtle in the trunk of my car. The giraffe road shotgun and the figures in their own cardboard boxes.

I delivered all the wax pieces into the expert care of Zach Gabbard at Mission Foundry . Zach had to further section the sculpture and then began making rubber molds for each part—legs, tail, flippers, head. Photos below are Zach’s.

He pours liquid wax into these molds to create exact replicas of the original forms. Once cooled and removed, the waxes are removed from the molds and assembled into intriguing structures, each one a selection of small waxes joined by a network of sprues — small wax rods that will later become pathways for the molten bronze. A central wax funnel, called a pouring cup, is added to the top to receive the metal during casting. These constructions appear like intriguing constellations or mobiles, their hidden shapes reveal themselves to the attentive eye.

The ganged group of sculpture parts are then dipped into a silica slurry, the liquid so fine that even fingerprints of the artist are captured in the surface. When the slurry dries, the assembly is dipped again, in all nine times. After each dip the piece is dusted with a dusting of fine sand and left to dry for a day. The construction takes on a hard skin. Layer by layer, the shell hardens, encasing the wax, becoming a ceramic mold. This process gives the shell strength needed to contain the heat of the molten bronze pour.

Then we arrive at the ‘Lost Wax’ moment. Once the shell has fully dried and hardened, it is placed in a kiln to burn out the wax, leaving the empty space — the negative of the original sculpture. With the mold still hot from the kiln, the bronze—molten and glowing— is poured down the funnel. It travels through the network of sprue channels, flowing into every facet of the now-empty shell. Once the bronze cools and solidifies, the shell is broken away, revealing the raw, fire-born metal.

There are still days of work ahead for Zach. He has to cut off the sprues, now solid bronze rods, and funnels, and check the pieces for any imperfections left by the mold. The chasing, so called, is a meticulous process of sanding and grinding, and welding the pieces together. Over the years of working together, Zach has come to know how to replicate the textures I sculpt in my wax sculpture, but he is doing it in metal. He understands the subtleties of the textures with the deliberateness of a poet.

I then return to the foundry to position each of the small bronze figures on the backs of the giraffe and turtle. Zach welded each one in place.

With the piece complete, Refuge is ready to receive its patina. Through heat and the application of chemicals—often oxides and salts—the bronze reacts and transforms once more, this time in color. Layers of fire and chemistry give the sculpture its final skin: a deep earthy brown-black with gold highlights.

Then Refuge received its final patina and wax polish. It’s a long process.

This piece is signed and numbered 1/5. Though my original waxes have disappeared, I have the molds to make four more copies. But always, for each one, we have to first make a new wax model, then cast it into bronze. After five copies, we’ll destroy the molds.

Refuge is on exhibit at the Art Complex Museum in Duxbury, MA. I’d love to send more casting work Zach’s way, so if you would be interested in a sculpture for your own garden, let’s talk.

Refuge, bronze, 2020