Today I live on a farm in Harvard, Massachusetts, where I tend the growth of three hundred apples trees, forty Asian pears, and a large fall raspberry crop. But fifteen years ago, I was an artist who lived in Groton with my husband and three children. Growing fruit was not on my radar, though like many New Englanders, we went apple picking every fall.

There was always a festive atmosphere of pumpkins, corn stalks, and apple baskets on Old Ayer Road in September. Hundreds of people came with their cars packed for a day in the country. A traffic cop directed the crossing as diesel tractors pulled hay wagons filled with families to different blocks of the orchard. Long lines formed at the farm-stand windows, and customers paid for their bags before heading into the trees for picking. We picked apples, climbing often to the top of that beautiful orchard.

Then one year, the orchard suddenly closed, and a sadness blanketed the hillside. The branches no longer blossomed in spring, and fruit no longer weighted the branches in fall. What was happening in Groton was no different than what was happening all over the country. In the United States, between 1900 and 2010, the number of farms decreased from 30 million to 2 million, a staggering tsunami of change.

Living in rural New England in the nineties, I had a first row seat to witness the disappearance of farmland from the landscape. The vanishing happened as quickly as a magician’s trick; an apple orchard became Orchard Lane with twenty-five new houses. A dairy farm became Easy Acres, a sub-division with forty duplexes. It was sad to watch and there was little I could do. However, when something bothers me, I find it appearing in my art. I put a notice in the local newspaper asking for donations of old agricultural tools for an artwork about the disappearance of farmland. From one small notice in the Groton Herald, the phone started to ring. People responded with warmth and generosity. Usually it was a single tool, a saw that had belonged to a grandfather, a scythe, or a treasured rake. One man offered me rough-sawn boards with sinuous edges.

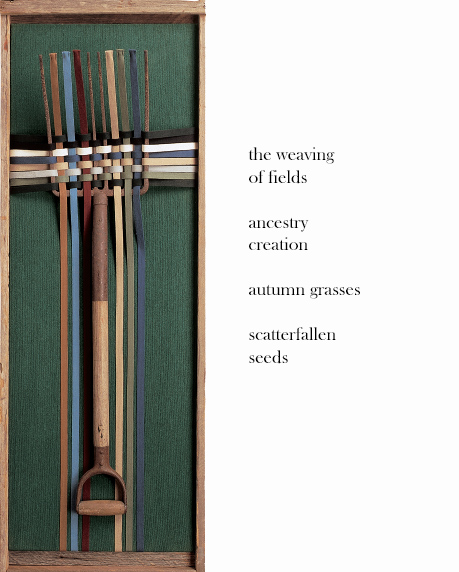

In little time, I had a collection of tools that evoked human effort, the sweat and muscle of hand labor. I took a heavy garden fork and a selection of colors from my box of Shaker tape, the remnant material from chair-making, a gift from the owner of Shaker workshops. I wove these colorful bands through the tines of the fork and wrote a poem to accompany the sculpture.

Common Land, LH

Another tool was a gift from a veterinarian in Groton. She gave me a five-foot saw with a mosaic of cutting teeth. I was definitely a ‘tree hugger.’ I hated to see trees taken down along town roads. I bemoaned electric wires that cut through their butchered canopies. There was a great tree in the common near the Nashua River. One day a large painted orange ‘X’ appeared on it. The next day, I spray painted that ‘X’ brown to match the bark and the state highway men drove right by it.

The second sculpture I made was Marked Trees, created with this five-foot saw blade, bands of green cloth, and long slivers of sawn wood.

green woods

old pasture

buried rust

the saw sharp

silence

of marked trees

I loved these tools and the stories they evoked. They brought out sorrow, loneliness, and longing. A wheel, a bucket, and an old piece of rope became the sculpture, Empty Barn.

Saving a woodlot is relatively easy; saving a farm is not as simple — you need a farmer.

Now, fifteen years later, I am an artist and a farmer with many old agricultural tools. Old Frog Pond Farm’s annual outdoor sculpture exhibit gathers artists from all over New England who celebrate the connection between art and the natural world in their work. The old agricultural tools no longer evoke sadness and loss; I work with them in the soil or plant them as sculpture.

The Juggler in the Orchard, An old cultivator and river stones. Photo: Ricardo Barros

Fifteen years ago I never imagined I would have brought a dying orchard back to health. When I put the intention to save farmland into my art, I didn't imagine I would become that farmer. I guess it’s important to know what you really want. What we really intend, does come true.