At the farm last Sunday, Stephen Collins performed a solo play about Walt Whitman, Unlaunch’d Voices, by Michael Z. Keamy. Whitman, as the play begins, grumbles about the poor reception for his book, Leaves of Grass — his life work, his own body, his soul! They didn’t even like the title, he complained. The critics pointed out that grass doesn’t have leaves, it has spears, and protested that the poetry was bombastic, egotistical, and vulgar. He garnered a few good, anonymous reviews, that is, written by himself. Today, Leaves of Grass is one of greatest songs of America. Take heart writers and artists! You may never know the value of the gifts you are offering.

Our performance was outdoors, the first time that Collins had performed in plein air. Collins, all 6’ 5” of him, flung his gallant arms to the sky and strode along the pond edge. At times I felt as if he might plunge in with a big splash, but he remained well-rooted to the ground. Collin’s portrait of Whitman resembled a great tree waving its leaves, encouraging, praising, admonishing, and loving all at once, a great giving creature.

Trees are giving creatures, too, turning carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into sugars. When the heavens provide enough rain, sun, and warmth, the tree makes lots of sugars. In fact, trees feed these sugars down to the fungi, which live attached to the roots. Later, if a tree calls for food, the fungi send any surplus back up. Trees are also companionable. Scientists have injected radioactive isotopes into a tree in order to follow the sugar flow and have watched it move down to the forest floor and up into the trunk of a neighboring tree.

Deciduous trees release their leaves in the fall. They rest for the winter, and then have to produce another full set of leaves in spring if they are going to survive. No leaves, and death comes quite quickly. Our apples trees have been stressed all summer from the drought. Early in the season we could irrigate, but then the wetlands' water level dropped too low, and the intake for the pump clogs with weeds. It’s good our apple trees weren’t carrying a load of fruit.

Macintosh Trees with no Apples, LH photo, Sept, 2016

In 2012, we also had no fruit. This was a puzzle to both growers and scientists. No one could quite pin down the reason, though many hazarded guesses. Now, once again, we have been in severe drought conditions, and the trees have no fruit. We had some blossoms in April, but it was much fewer than I would have expected (even taking into consideration the 2015 bumper crop). We had bitter cold in February, which is when New England lost the peach crop, and then the freeze in April seemed to have taken the apple blossoms. That’s one way to explain why we have no apples, but I think there is something else we don’t know about in the equation.

Something that the trees know.

Who is to say that the trees didn’t see severe drought crawling towards us long before we experienced it, and they did what they needed to do to prepare? They let go of their possessions, their precious fruit, and kept their leaves so they could sustain themselves through the desert conditions. We are only beginning to discover the wisdom in leaves and trees. Scientists recently found that when a tree is dying, it will get rid of its excess carbon by sending it to a healthy neighbor.

There is equally great wisdom in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass:

This is what you shall do; Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to everyone that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God . . . read these leaves in the open air every season of every year of your life, re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and your very flesh shall be a great poem . . .

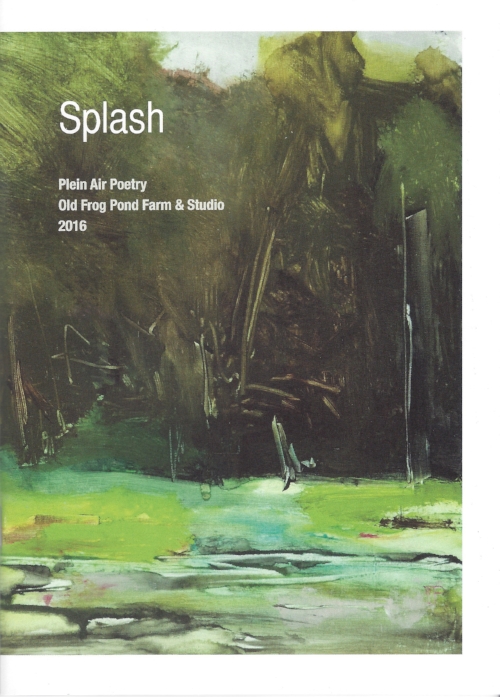

This week our Sunday afternoon farm event is the 4th annual plein air poetry walk. The poets of Old Frog Pond Farm will gather to walk the land and read their poems at the sites that inspired their leaves. Splash is this year’s theme — join us at 2pm — as organizer Susan Edwards Richmond leads us around the pond and through the orchard.

I have never

bent grateful

as this blade of grass,

bearing the hiss, ping ping

sound of insufficient blessing

on my naked, needy back.

—from the poem “Hiss, ping, ping” by Lucinda Bowen

Cover of "Splash Plein Air Poetry", Painting by Martha Wakefield