“One of the most calming and powerful actions you can do to intervene in a stormy world is to stand up and show your soul.”

—Clarissa Pinkola Estes, author of Women Who Run with the Wolves

It is Saturday morning as I write this blog in Kona on the Big Island of Hawaii. I am here with my partner, Blase, to visit my son, Nick who lives here. It feels like everyone else I know is either readying for walking in one of the Women’s Marches or despairing about the inauguration. Since arriving in Kona two days ago, the ocean swells have been several times normal. Driving along the rocky coast Nick can’t keep his eyes on the road as he is drawn to watch the surf breaking in high waves along beaches and inlets that are usually quiet. We stop often to watch and photograph.

As I write on a terrace where I can see the breaking waves and hear the chorus of forceful, soulful, singing; I hear the energy of Martin Luther King breaking into our collective longing with I Had a Dream. I think about what I can do in the upcoming days, and weeks, and months with this new world order. I think about what we can each do to shine our light, to fan the embers and make them glow.

On our first day we drove to the southernmost tip of the Big Island, the southernmost point of the United States. The trees grow horizontal, their branches pulled as if by some invisible force, an unceasing tug of war between the fierce thrust of the constant wind and the need for the tree to remain rooted. it felt like an apt metaphor for the position so many of us feel we are in today.

Yesterday we drove the opposite direction, to Popolu in the north, a rough, ragged beach with boulders and rough seas, that sits at the end of a valley between two great ridges.

Nick led us down the steep trail, knowing at the bottom some of his friends were already there. They had strung a hi-line between trees in the woods behind the beach. A hi-line is a slack rope, and theirs was set so that you had to walk over a ravine. We watched as one man, strapped with harness and clipped onto the line so he couldn't fall to the ground, began. Body erect, arms shifting side to side, torso adjusting with each minute waver of instability, countering, moving from instability to stability to instability, never a moment of settling into inactivity. He knew how to walk the distance, he’s been walking the hi-line for a while, but had always feared the line when there was a deep crevice to cross. It takes immense concentration to simply step up and balance on a slack rope. You never look down, you must breathe and relax, and fiercely keep your point of focus. I watched his intense physical and emotional single-minded attentiveness with awe. He had to quiet the uproar of fear or he would fall.

A young woman was up next. He reminded her, “We are here to challenge ourselves, to go where we most fear.”

What do I fear most? That is the question I will carry with me. At each moment what am I fearing? Because if I am fearing, then I am not loving. And there are only these two possibilities. There are infinite ways to carry the light. It is up to each of us to be uniquely ourselves and bare our souls. There are no shoulds, no instruction set for how to step forward; we are each on our own unique hi-line. But some of the same guidelines apply — concentrate, relax, give in, forget the self, and go for it. And perhaps most importantly, never forget to focus on what matters most to your own soul, because that will be the truth and that will kindle the flame for others.

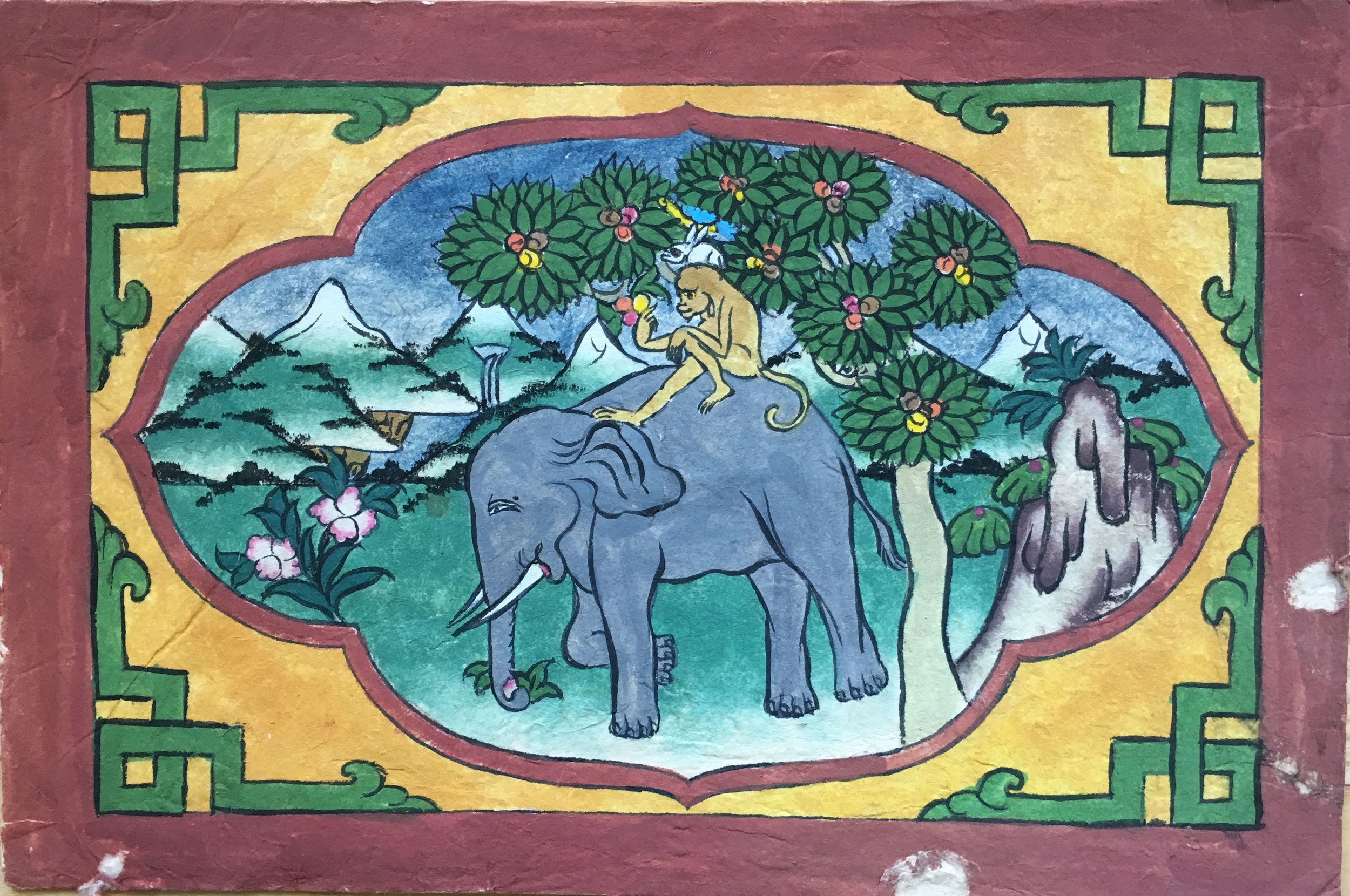

Judith Taisei Schutzman at the Boston March